The ICO is Reviewing its Approach to Public Sector Fines: What Should it Decide?

Table Of Contents:

Data breach fines are on the rise. According to the ISMS.online State of Information Security Report 2024, the average fine amount responding businesses reported last year was up nearly 4% annually to £258,000. Yet this study only takes account of the finance, healthcare, manufacturing, retail and technology sectors. In the public sector, data protection regulator the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has trialled a lighter-touch approach to fines for two years.

A decision about whether to continue or take a harder line on enforcement is pending in the autumn. The evidence suggests a rethink is necessary.

Two Years Of Pulling Punches

An analysis of ICO fines by URM Consulting highlights the stark difference in regulatory approach between the public and private sectors. Of 29 reprimands issued to organisations last year, 20 were levelled at the public sector. However, all 17 were issued against private enterprises when it came to fines.

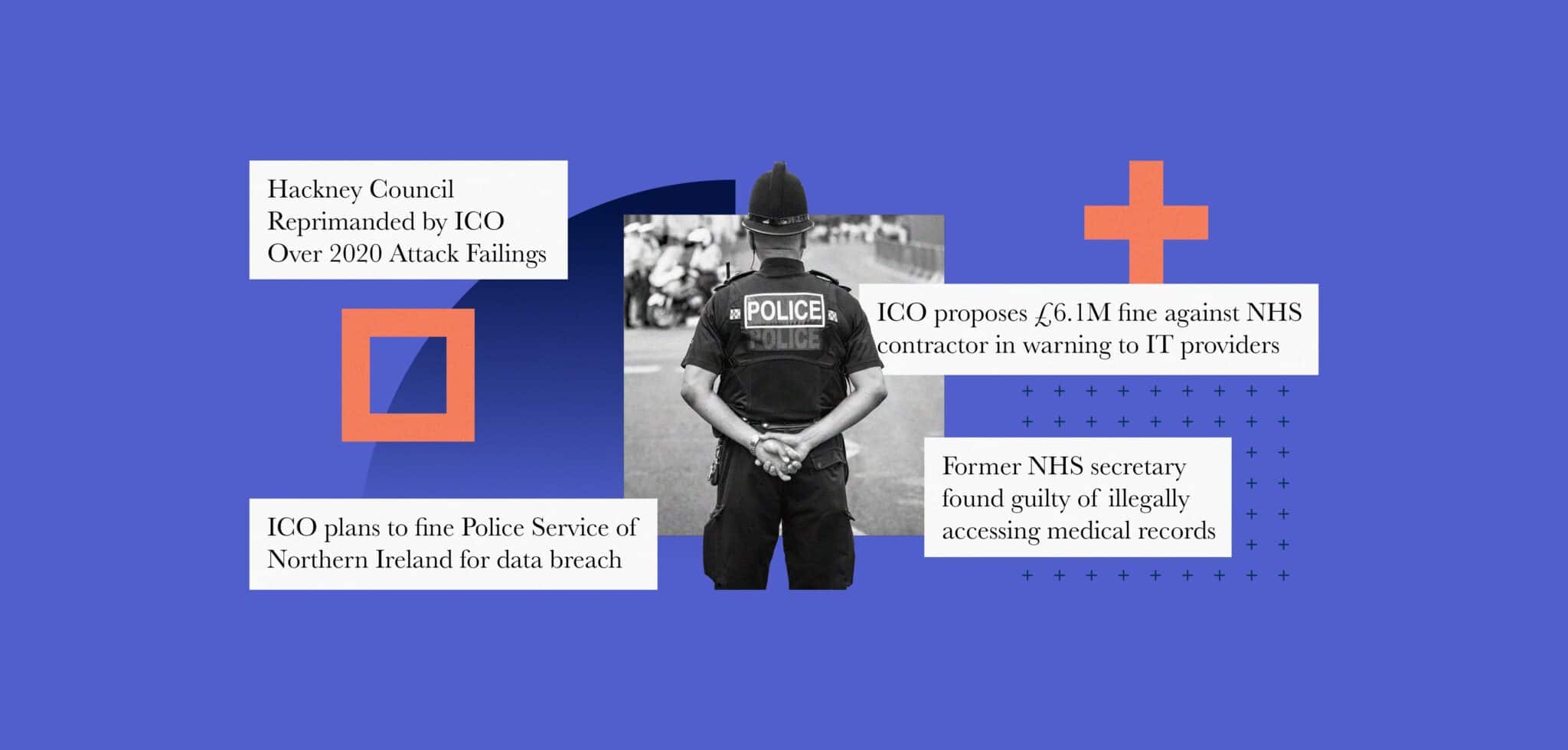

Among the most noteworthy examples of the ICO pulling its punches with public sector fines in the past two years are:

- The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), which accidentally leaked sensitive information on officers in what has been described as one of the worst breaches of its kind, given the sensitivities surrounding the police force. Yet, although the lives of serving officers and their families were arguably put at risk, a possible fine of £5.6m was reduced to £750,000

- The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, which accidentally disclosed the email addresses of 1,781 Gender Identity Clinic patients, some of whom were publicly identified. A would-be fine was slashed 900%+ to just £78,400

- The Cabinet Office, which exposed the names and unredacted addresses of more than 1,000 people announced in the New Year Honours list, including various celebrities. A £500,000 fine was reduced to £50,000

- The Ministry of Defence (MoD), which leaked via email highly sensitive information on people seeking relocation to the UK after the Taliban took control of Afghanistan. A £1m fine was slashed to £350,000

- NHS Highland, which emailed 37 people likely to be accessing HIV services, sharing their details with each other. A fine of £35,000 was reduced to a mere reprimand.

- The Electoral Commission, which allowed hackers to access information on 40 million citizens after a series of basic security failures. It was not fined at all but simply received a reprimand.

Why Is The ICO Going Easy?

Last year, more UK businesses were fined between £250-500K (26% versus 21% in 2022) and between £100K-250K (35% vs 18%) than in the previous 12 months, according to ISMS.online data. Yet the public sector escaped. That’s despite worsening data breach statistics in government. According to the ICO’s own data, analysed by law firm Mischon de Reya, there was a staggering 8000% increase in the number of individuals impacted by data breaches in central government between 2019 and 2023. Unbelievably, there were 195 million individuals affected by breaches related to “economic or financial data” in 2023 alone, nearly three times the population of the UK.

So why the change in ICO policy? For information commissioner John Edwards, it boils down to the fact that fines will likely change private sector behaviours more readily than in the public sector. And the fact that government finances are already stretched dangerously thin.

“I am not convinced large fines on their own are as effective a deterrent within the public sector. They do not impact shareholders or individual directors in the same way as they do in the private sector but come directly from the budget for the provision of services,” he wrote in June 2022.

“The impact of a public sector fine is also often visited upon the victims of the breach, in the form of reduced budgets for vital services, not the perpetrators. In effect, people affected by a breach get punished twice.”

Yet the logic on fines as a deterrent is a bit woolly. ISMS.online research finds that only a fifth (19%) of responding businesses say their primary motivation for compliance is to avoid penalties. Far more talk about remaining competitive (34%), increasing customer demand (34%), and protecting business (30%) and customer (29%) information. None of these other motivating factors are particularly relevant to the public sector, leaving fines as one of the few levers available to the ICO.

Compounding the confusion is the fact that there are mixed messages coming from inside the ICO itself. John Edwards was only recently reported as saying that his policy of not fining the public sector but instead issuing non-binding reprimands was ”very effective, especially in the public sector where reputation is worth more than the purse”. However, he has since admitted that there’s limited evidence available even to assess the impact of monetary penalties on the sector.

“I would expect the upcoming review to have some data and other evidence considering, for instance, whether the ICO has seen any evidence of an improvement in compliance in the public sector as a result of the public sector approach,” Mishcon de Reya senior data protection specialist, Jon Baines, tells ISMS.online.

“Anecdotally, I would say we have instead seen poorer compliance. I continue to be unconvinced that there is any basis to treat the public sector any differently than any other sector. I fear that the ‘public sector approach’ has the effect of fettering the ICO’s discretion to take effective, proportionate and deterrent action.”

Room For Improvement

So what happens next? Baines explains that, prior to the GDPR, the ICO used to require a data controller to sign an “undertaking” to make improvements – if their organisation was found wanting but a fine or enforcement action were not justified.

“I see no reason why the ICO could not resume this approach in appropriate cases: it would have the effect of imposing obligations on senior managers to ensure that their promise is kept. In my experience, those ‘undertakings’ were very effective at concentrating those senior managers’ minds on the importance of data protection compliance,” he adds.

“I would also suggest that the government considers whether it might want to confer formal powers, through legislation, on the ICO to seek such undertakings, with the possibility for sanctions against individuals – as well as organisations – if the undertakings are broken. I think that it would then have a suite of powers available which, singly or in combination, could be effective.”

Amid this confusion, the best way for public sector organisations to take control of their destiny is to proactively mitigate breach risks. The ICO has helpfully highlighted the things that both public and private sector firms should be doing in this regard. It has previously taken action against organisations that have failed to:

- Deploy multi-factor authentication (MFA) on external connections.

- Log and monitor systems and act when there’s unexpected exfiltration of data or RDP connections

- Act on endpoint alerts such as those produced by anti-malware tools

- Use strong and unique passwords on internal accounts – especially privileged accounts.

- Patch known vulnerabilities.